I read about an enormous oak tree and it changed my life

Original article by thetimes.com

Serge Arnaudiès realised the “magnificent cork oak” he had read about was in Reynès, beside land his family had farmed since the 17th century

DAVID CHAZAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

A century-old memoir led Serge Arnaudiès on a quest to save a solitary oak in the French Pyrenees and secure its place in history

Browsing in the Perpignan flea market one Sunday morning in 1990, Serge Arnaudiès happened to pick up a hundred-year-old travel memoir that would change his life.

Leafing through its yellowing pages, he was intrigued by a description of a “magnificent cork oak” in Reynès, beside the land his family has farmed since the 17th century in the foothills of the eastern Pyrenees. He had never noticed the tree, but he started combing the wooded hills around his farm, using the book to guide his quest.

GEORGES BARTOLI/LE MONDE

“I was determined to find out if it was still standing a century later,” he said. “I knew it must have grown even bigger. I began searching, and eventually I found it, surrounded by brambles and hawthorns. I decided then and there to buy the land where it stood. I saw it as my duty to look after it.”

Browsing in the Perpignan flea market one Sunday morning in 1990, Serge Arnaudiès happened to pick up a hundred-year-old travel memoir that would change his life.

Leafing through its yellowing pages, he was intrigued by a description of a “magnificent cork oak” in Reynès, beside the land his family has farmed since the 17th century in the foothills of the eastern Pyrenees. He had never noticed the tree, but he started combing the wooded hills around his farm, using the book to guide his quest.

“I was determined to find out if it was still standing a century later,” he said. “I knew it must have grown even bigger. I began searching, and eventually I found it, surrounded by brambles and hawthorns. I decided then and there to buy the land where it stood. I saw it as my duty to look after it.”

“There was no way I was going to leave this part of our natural heritage uncared for and unloved,” he told me last week while taking refuge from the languid afternoon heat in the shade of the tree’s vast emerald crown.

Three to four hundred years old, the tree he calls le Grand Chêne, the Great Oak, has outlived kings and emperors. It survived the upheavals of the French Revolution, but it only narrowly escaped the chainsaws of 20th-century property developers before he rescued it from oblivion.

“Saving it for posterity became my life’s mission,” he said. “I got lucky because a plan to build housing on the site had just been shelved, so I managed to buy the land from a developer.”

DAVID CHAZAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

He paid 200,000 francs (about €35,000) for the 7.5-acre plot in 1990, 100 years after the publication of the book that ignited his passion: Voyages aux Pyrénées: Souvenirs du Midi par un homme du Nord (Journeys to the Pyrenees: Memories of the South by a Man of the North), by Victor Dujardin.

Arnaudiès, now 70, rejects any suggestion that he has become obsessed with the Great Oak, but he clearly regards it as a reassuring symbol of continuity as traditional patterns of rural life disappear due to climate change.

Gazing out over the deceptively green hills that mark the border with Spain, the recently retired fruit farmer lamented that worsening droughts had prevented him from passing on his cherry, peach and apricot trees to his son, Étienne, 43. Lacking water for irrigation, he has been forced to rip them up. He squinted up through gnarled boughs at clouds gathering above the Pyrenees.

“It rained a bit this morning for the first time in months, but it’s finished now and it wasn’t enough,” he said. “A lot of vineyards around here have also been torn up. Our future will be tourism.”

Arnaudiès has adapted by opening a gîte.

Back in 1990, his first move as the Great Oak’s owner was to clear a path to make the tree accessible to the public. There was no entry charge and that remains the case today. Arnaudiès has never sought to make money from the find.

Allowing visitors in is a way of ensuring it is preserved for future generations, he said. However, the Great Oak is an increasingly popular tourist attraction that might help to keep the local economy afloat.

Jean-Jacques Méric, a 74-year-old Parisian, said he was on a beach holiday more than 200 miles away on the Atlantic coast when he read about Arnaudiès and the tree. “We decided we had to come and see it,” he said. “It’s a beauty. Well worth the trip.”

When I told him the Great Oak was to feature in The Sunday Times, he joked: “I hope no one will come over from Britain and chop it down like the Sycamore Gap tree.”

Another visitor, Gabriela Trujillo, 43, from the Chartreuse region in eastern France, said: “If you travel to visit museums, surely it’s worth making a journey to see a wonder of nature?”

Arnaudiès and his wife, Martine, regard the tree “like a member of the family”.

Pictures of the Great Oak and news stories about his efforts to protect it are included in their family album alongside photographs of their son and grandchildren.

With his wife, Martine, and a photo album of the Great Oak

DAVID CHAZAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

Thanks to the path he has created, parties of pupils and holidaymakers come to picnic under the tree, and couples are said to have got engaged beneath it. He does not strip its bark for cork, which he could sell, because he is worried it would cause stress that might kill the ancient tree. “If it outlives me, my son will look after it,” he said.

Its elevation to record-breaking status began in 2021 when Arnaudiès read in a magazine that the world’s tallest cork oak was in Portugal. He was convinced that his Great Oak was bigger. He and his wife travelled to Aguas de Moura in southwestern Portugal to size up the rival, known as the Whistler Tree, officially named the Sobreiro Monumental. It had been voted European Tree of the Year in 2018.

“It is a magnificent tree, but there’s no doubt that it’s smaller than ours,” Arnaudiès said. “We were determined to set the record straight.”

They contacted Guinness World Records, which sent a team to measure their tree.

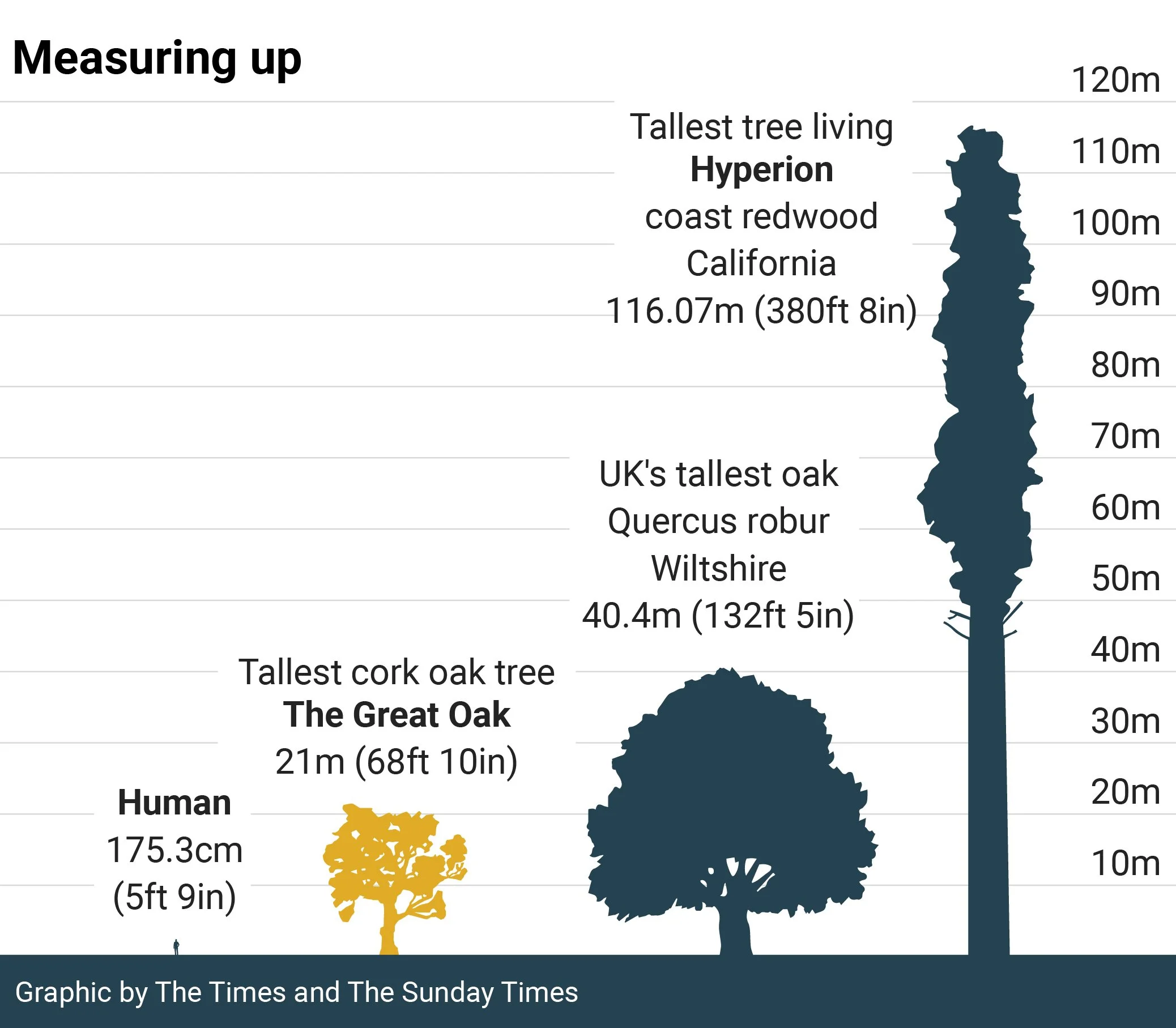

They “certified that the height of the Great Oak was 21 metres [68ft 10in], about the same as a seven-storey building,” he added. The Portuguese tree stands at 16.2 metres.

Amanda Ireland, 65, a British expatriate who lives five minutes’ walk from the tree, said: “There’s a lot of pride here that the biggest cork oak is in France, not in Portugal or Spain. It’s nice for people to come and discover how beautiful the countryside is here, so long as the numbers remain within reason.”

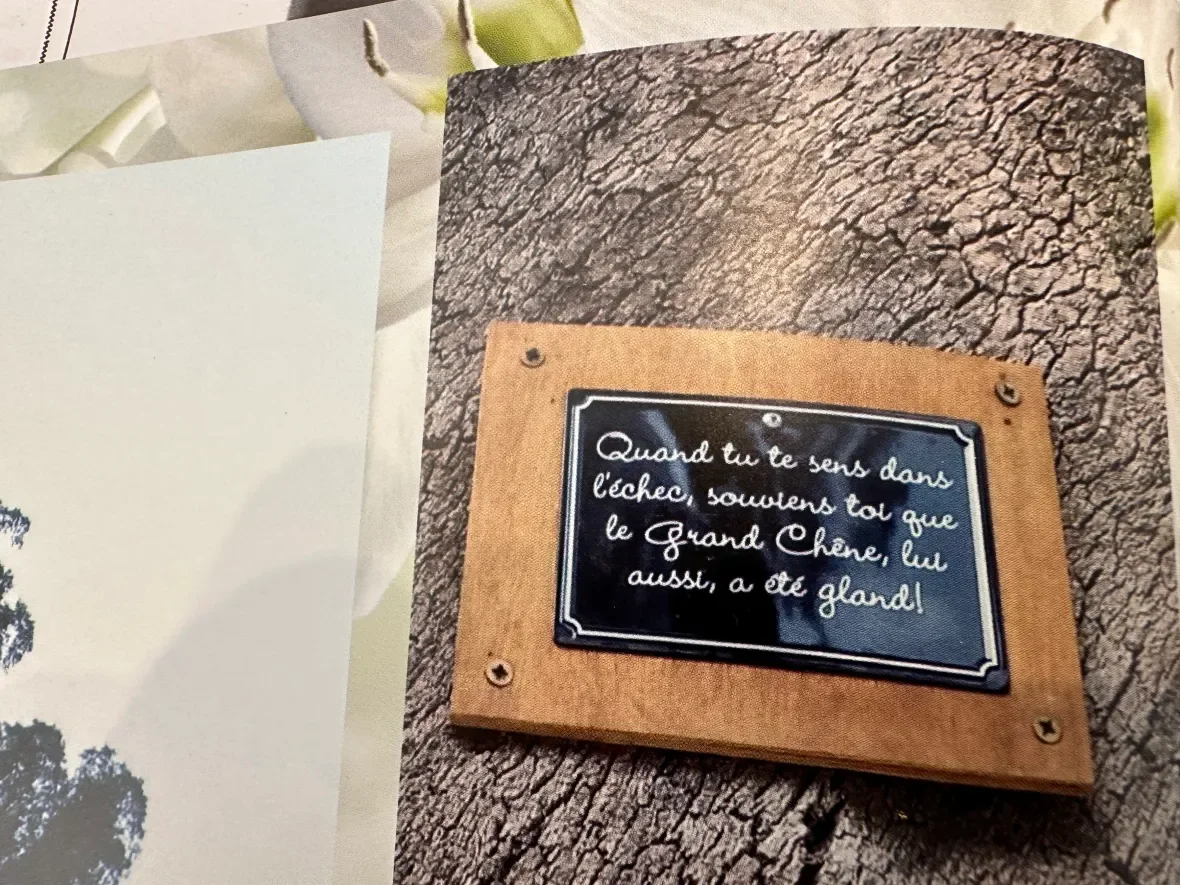

Arnaudiès has just one small regret. A wooden plaque he had placed on the tree has mysteriously disappeared.

Inscribed with an adage inspired by the sixth century Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu, it read: “If you aren’t getting what you want, remember that even the Great Oak was once just a little acorn.”

A plaque installed on the tree has disappeared

DAVID CHAZAN FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES